St Mary le Port: a Bristol planning case study

Political interference, specialists sidelined and developer power: office block scheme at the historic heart of the city reveals important insights into Bristol's planning and development regime

“The determination of a planning application is a formal administrative process involving:

- the application of national and local planning policies

- reference to legislation, case law and rules of procedure

- rights of appeal and an expectation that the local planning authority will act transparently, reasonably and fairly.”

Local Government Association and Planning Advisory Service, ‘Probity in Planning’

“The bombing destroyed much of the old town north of Bristol Bridge, now laid out as Castle Park, and great swathes of inner Bristol…the physical and psychological effects of the bombing cannot be over emphasised and possibly still informs the apparently passive approach to development today. There is a strong sense of the Bristol that was lost that can never be re-created, which excuses indifference to the pernicious impact on the cityscape of deregulated capitalism over the last 30 years.”

Adrian Jones, Towns in Britain: Jones the Planner, ‘Bristol Fashion’

“Some have raised concerns that we have got involved in planning. We have. We’ve been elected to shape the city and the outcomes we want cannot be left to the chances of a developer aligning with an out-of-date Local Plan and a quasi-judicial process.”

Marvin Rees, Mayor of Bristol

There is increasing public anger at the way the planning system has been operating in Bristol. This has been brought to the fore in recent months by what’s become known as the ‘Broadwalk scandal’ - the reversal of a unanimous decision by a cross-party planning committee to refuse plans for a ‘hyperdense’, 12-storey mixed-use scheme in Knowle that provided less than 10% affordable housing. This reversal was facilitated by sudden U-turns from the three Labour councillors and a behind-the-scenes collaboration between the committee Chair, the Head of the Mayor’s Office and the scheme’s developers. It’s led to public demonstrations from the local community outside City Hall, the early stages of legal action and the resignation of a Green councillor from the planning committee in protest. It also helped inspire a petition which received over 3500 signatories stating that they had lost confidence in Bristol’s planning system, which meant the subject was debated at a meeting of Full Council.

Planning can be seen as dry and technical but it has a profound impact on shaping the places we live and how they in turn shape us. It also provides an insight into the forces that are in control of shaping those places. Despite the planning system’s status as a ‘quasi-judicial’ process, planning is by its nature deeply political. And because land and property are key motors of wealth accumulation and economic growth, is powerfully influenced by vested financial interests. This means the planning system also acts as a window on the efficacy of the legal and democratic frameworks that are supposed to protect the public from concentrations of power and provide some accountability over what happens to the places in which we live.

Some of the problems with the planning system in Bristol are issues that are affecting local authorities nationwide. Many local authority planning departments are under severe strain across the country after over a decade of funding cuts from central government. They struggle to retain good, experienced staff. Long backlogs have built up. This has been particularly acute in Bristol.

But the Broadwalk controversy has brought to wider public attention issues around planning and development in Bristol that are specifically about political influence. In large part, these concerns are related to the mayoral system that was brought in to govern the city in 2012. They focus particularly on the current mayor Marvin Rees’ perceived lack of concern with good design and placemaking, in his creation of an environment in which developers hold sway, that sees behind-the-scenes sweetheart deals, local communities ignored, and the undermining of statutory planning processes that are supposed to ensure the democratic legitimacy of decision-making and controlled, policy-compliant development.

In an important sense, mayoral systems are designed to do this sort of thing. Rather than acting to devolve power to local communities and strengthen local democracy, as they’re often sold as, their main function is to provide a stable governance model that will encourage inward flows of capital. Developers and investors like it. With a long history in America, it’s a model whose most persistent advocate in Britain has been former Conservative Cabinet Minister Michael Heseltine - the member of the Thatcher and Major governments who privatised more industries than any other. For Heseltine, city mayors act as a way to drive economic growth and circumvent the messiness of local politics. First instigated by New Labour with the Mayor of London role, it was the Localism Act 2011, introduced by David Cameron’s coalition government, that saw referendums for city mayors take place across the country the following year. In the end, however, the only core cities to decide to take up the option were Liverpool and Bristol.

In Liverpool, a major corruption scandal saw the mayor Joe Anderson arrested along with several senior council officers. A damning report by government inspector Max Caller exposed an unaccountable bullying culture, the handing out of dubious contracts and dodgy deals over land and property. It led to commissioners being sent into the council to take over functions such as highways, property and regeneration. Not unrelatedly, a wave of crass development on the historic waterfront that happened during this period also led to UNESCO removing the city’s world heritage status. The council voted to scrap Liverpool’s mayoral position in July 2022.

The same year in Bristol, a citywide public referendum brought about by opposition parties (most crucially the Greens, who came to have as many seats on the council as Labour following the 2021 local elections) was won with a 59% majority voting to replace the mayoral model with a committee system. Rees had previously said that he would step down at the end of his second term in May 2024, but the mayoral system he has long promoted as the best form of city governance, now goes with him.

Rees’ administration hasn’t been implicated in the level of malfeasance exposed in Liverpool, but part of the reason for the referendum vote going against the mayoral model was the maximalist approach he took with it. After initially claiming that he would govern in a similar style to predecessor George Ferguson - the first elected mayor from 2012-2016, who ran as an independent and put together a cross-party ‘rainbow’ Cabinet - after 18 months, Rees replaced all councillors from other parties with pliant Labour loyalists. The One City approach, established at the outset as the central policy apparatus of the administration, and codified in 2019 with the One City Plan, has also sought to create a governance model that sees large institutional ‘partners’ such as the universities, along with the business community, “coming together to agree the city’s priorities; manage and deliver them together”.1

The sidelining of democratically elected councillors under this system was publicly criticised by several departing Labour councillors at the end of Rees’ first term in office. This included experienced Cabinet member for housing Paul Smith, who said in 2020 that “more checks and balances” were needed on the Mayor’s power and that he “would hate to come on the council as a backbench councillor now because the amount of authority they are able to exercise is incredibly limited.”2

The powerful central command of the Mayor’s Office over the running of the council has gone alongside a PR operation that seeks to establish the authority of the mayor through slick social media content and managed, set-piece public appearances. An effort to attack and denigrate local journalists has run alongside a culture of secrecy that’s aimed to frustrate scrutiny and democratic oversight from both councillors and the public. Between 2020 and 2022, Bristol City Council had the second most complaints to the Information Commissioner’s Office of any local authority in the country about the handling of Freedom of Information requests, and has now received a formal censure from the regulator.

Following the referendum, a further blow came for Rees in August 2023 when his attempt to become an MP was thwarted by local Labour party members in north-east Bristol who voted to select an alternative candidate. As the first directly-elected European mayor of black African descent, in a city with a shameful history of involvement in the slave trade, and as a local man who’d grown up in difficult circumstances, there had been significant goodwill towards him at the outset. A willingness to align himself with the hopeful rhetoric of the new Corbyn project had also ensured enthusiasm and a large turnout on election day in 2016. But along with concerns around local democracy and development, a high-handed and rather charmless personal style has left Rees without much warmth of feeling across the city as his time in office draws to a close.

Technocratic and dogmatic, inclined towards the portentous cliché, his public utterances often seem pulled straight from a business management presentation or a Bloomberg Harvard City Leadership seminar. It’s a style that doesn’t appear to have connected in any meaningful way to the public beyond the professional managerial class that have some direct investment in the city’s governance - and who hear in him a man who speaks their language. For those that take an interest in what happens in the council chamber, the often desultory and condescending manner he engages with opposition councillors and members of the public has further eroded his standing.

The time Rees has spent on the international circuit or working for other organisations has also become a source of grievance. Between September and December 2023, he could be found at various times on conference platforms in New York, Kigali, Geneva and Dubai. These trips are justified - both in time away from running the city and in fossil fuel emissions - as ‘putting Bristol on the world stage’ but the benefit is often judged to accrue primarily to the mayor himself. The fact that there is now a West of England metro mayor for the wider region, with a confusing overlap of authority, only added another reason for scrapping a position that many had come to feel concentrated too much local power in a single ego.

The broader political and economic context of the mayoralty, however, has been over a decade of savage funding cuts to local authorities from central government. A 27% real-terms cut in core spending power since 2010, while demand for key services such as adult social care have risen, has left councils across the country struggling to provide their basic set of statutory services. For all the executive power granted to a city mayor, the constraints of austerity mean there are many things they are largely powerless to affect, let alone improve. The desire to be dynamic and re-shape the city, focuses instead on working with the private sector to bring about investment and regeneration.

But whereas in other areas the executive struggles with a lack of financial resource, with planning and development it finds itself constrained by law. The Local Government Act 2000 is the piece of current legislation that sets out the separation of powers between a council’s planning department, acting as the Local Planning Authority (LPA), and its executive, which in Bristol under the mayoral system is the Mayor and his Cabinet. The LPA is responsible for carrying out the planning functions of the city under the Town and Country Planning Act. And by law their determination of planning applications - with delegated powers to councillors on cross-party committees for major, or particularly controversial, applications - is dictated by the local development plan, the statutory documents that set out the policies specific to the city, and the National Planning Policy Framework (NPPF), the national set of standards produced by central government. These are the material considerations all new development proposals are assessed against.

In his first State of the City address in 2016, Rees told a story about his entry, as a newly elected mayor, into what he called “the weird and wonderful world of planning in Bristol”.3 He had apparently been surprised and dismayed when council officers told him that planning decisions weren’t down to him but directed by a combination of national and local policies, “that sits above all of us, our managers and our elected politicians.” It led to the following conclusion:

“My first port of call is to overhaul the local policies to make sure it delivers for Bristol…it’s become clear to me that this is how you start to draw your own picture of the city.”

This was put into action a few months later in early 2017 with the start of a review of Bristol’s Local Plan. And although it hadn’t been a talking point during his campaign to become Mayor, he went on to say in that first State of the City address:

“I want Bristol’s skyline to grow. Years of low level buildings and a reluctance to build up in an already congested city is a policy I am keen to change. Tall buildings built in the right way, in the right places and for the right reasons, communicate ambition and energy.”

There was no further detail about this new policy in the speech beyond the vague aspiration to “communicate ambition and energy.” But it soon became aligned with the housing crisis, with housing identified as a key political priority from the outset of Rees’s administration. In 2013, house prices in Bristol had started to rise more rapidly than the national rate, which was itself, already rising fast. With the city constrained by Green Belt to prevent urban sprawl, the logical argument put forward was that increased densification on centrally located brownfield sites was the way to increase the supply of much-needed new housing.

This also fitted with a consensus view about the sustainability of cities in an age of climate change. City centre living is seen as key to moving away from car dependency, with walking, cycling and short journeys on public transport becoming the natural alternative. Despite the well-documented higher embodied carbon of tall buildings, and the fact that they often don’t make the most efficient use of land in terms of densification, they were equated with meeting the challenge of a growing city - as well as acting as a visible signal to investors that the city was open for business.

Whatever the governance model, running such a complex city, riven with stark divides on economic, cultural and racial lines, that map equally starkly onto the geography of the city, is certainly far from straightforward. In one sense Bristol is, as Adrian Jones says, “very definitely a southern city with a dominant bourgeoisie and middle class sense of entitlement”. Its lively arts scenes, bars, restaurants and nightlife, combined with its dynamic topography, human-scale cityscape, and proximity to attractive countryside, pulls in professionals from London and elsewhere. Outside London, it has the highest rate of graduates wanting to stay where they studied. With a diverse economy that has been able to adapt relatively successfully to the UK’s post-industrial settlement, its strength in high-value sectors such as advanced engineering, financial services and digital tech, mean that of all the core cities it has the highest average weekly earnings, the highest employment rate, and the highest productivity measured in Gross Value Added (GVA) per hour.

The city famously has a strong alternative culture, wreathed in weed smoke, which tends to unduly shape its image to outsiders. And there is a substantial liberal, ‘green’ middle-class. Many lower-middle and working-class communities are getting by in relatively decent circumstances. But there is another side of the city that the tourists visiting its regenerated harbourside, and the moneyed inhabitants of Clifton and Stoke Bishop, rarely encounter. Around 15% of Bristol’s residents (roughly 70,000 people) live in the most deprived 10% of areas in the whole of England. This includes recent international arrivals in its ageing inner city tower blocks and longer established communities in Victorian neighbourhoods that are under attack from gentrification. And on the northern, and particularly the southern fringes of the city - where three neighbourhoods rank in the lowest 1% for deprivation in the whole of England - a left-behind, largely indigenous underclass live as far from the bright lights as you can get. The average life expectancy for a man in Hartcliffe is around 8 years less than those who live in the affluent inner suburbs that spread across the limestone slopes north of the city centre.

And in the centre, a rapidly expanding student population from its two large universities is increasingly having an impact. In the five years up to 2021/22, university student numbers increased by a third and there are now around 44,000 full-time students in the city. About a quarter of these are foreign students and it’s a percentage that’s set to rise as both universities increasingly look to that higher fee-paying cohort. It’s been a major factor in Bristol having the second highest population growth of all the core cities in England and Wales over the last decade, growing by an estimated 45,800 people.4

Following decades of population decline in the second half of the twentieth century, and a plateau in the 1990s/early 2000s, Bristol now has more inhabitants than ever before at around 480,000. And though there had been a marked decrease in the rate of population growth since the Brexit referendum in 2016, the 12 months to mid-2022 saw the second highest jump since records began, with a net increase of 7,700 people. The council’s data shows that this was largely driven by international inward migration, much of it non-EU students.5

This all means that the national crisis of house prices and rents outpacing earnings is particularly acute in Bristol, which now has the worst affordability ratio of all the core cities. Over the last decade, average house prices have increased by almost 90%, compared to a national average in England and Wales of 51%. In the last five years rents have soared by 41%, compared to a national average of 14%. There are now over 20,000 households on the waiting list for social housing and every night nearly 3,000 people are homeless according to the charity Shelter, with many dozens sleeping rough across the city centre.6

Marvin Rees’ election pledge in 2016 was for 2000 new homes a year, 800 of which were to be ‘affordable’, and there was strong political pressure to reach those targets. In order to get developers building more quickly a new ‘threshold’ approach to viability assessments - the test to establish the financial viability of developments to deliver affordable housing - was introduced in 2018, meaning that a proposed residential development in inner city areas with 20% affordable units wouldn’t have to undergo a viability assessment. The previous target had been 40%.7

This change went together with the introduction of a new Supplementary Planning Document (SPD) called ‘Urban Living: Making successful places at higher densities’.8 It replaced a 2005 SPD on tall buildings that had set out rigorous criteria for assessing the quality and siting of new proposals. With the laborious process of creating an entirely new local plan a work of many years, this new document was the method by which new material considerations used in the assessment of planning applications for tall buildings could be quickly introduced. Tasked with overseeing its creation, and given the spatial planning portfolio in Marvin Rees’ Cabinet in 2017, was new Labour councillor, Nicola Beech. Beech had come straight from working for developers in the planning process at the lobbying and PR company JBP.

These changes have led to a development boom, with developers and investors already attracted by Bristol’s economy, now given greater leniency and full encouragement to come and build - and build up. But what this has been providing in terms of housing is largely expensive market-rate flats (increasingly limited to Build-to-Rent, rather than for purchase) and purpose-built student accommodation. Building tall buildings is much more expensive in terms of construction costs, meaning that these developments rarely end up providing many affordable units if the developer can show it isn’t viable for them to make a healthy profit margin - often after they’ve paid very large sums for the land in the first place. They also rarely have many aesthetic qualities, with developers knowing that the need for housing will trump what are considered to be less important considerations.

Rees’ administration almost reached their target of 2000 homes of all types a year but in 2022/23 only 309 ‘affordable’ units were built across the whole city, following a peak of 474 the previous year.9 Even before you contest the real meaning of ‘affordable’ here (80% of a hugely inflated market rate), it’s a long way from the 800 a year promised in the election campaign of 2016. And though part of a bigger story of national failure, while the housing crisis has been declared the key priority of Rees’ administration, all of its measurable impacts in the city have got worse during his eight years in office.

Meanwhile, the developer-friendly push to ‘build up’ has begun transforming the city centre. The first major statement on the skyline of this new approach was Castle Park View, a residential development built on council-owned land that included a 26-storey, Build-to-Rent, high-rise tower, making it the tallest building in Bristol. The developers were apparently encouraged by the administration to add ten storeys to their original plans to create what they called a ‘landmark’ building. A video posted on the mayor’s official social media accounts in April 2019 shows an enthused Rees in hard-hat and hi-vis on the building site as the first piling work is being done. He says to camera:

“An amazing morning here for us. A hugely symbolic morning…Getting this site moving, some iconic buildings coming up. But not just in terms of buildings but in terms of getting things done and bringing forward this site that the city’s been looking at for years. And my hope is it really is a symbol of the momentum we have going now in Bristol.”

“Getting things done” (or “getting stuff done”) has been the continually repeated mantra of Rees’ administration. And while services continue to be cut, one thing that certainly has been happening is big new developments. Bristol currently has over thirty high-rise schemes recently built, permitted, or going through the planning system.10 These include proposals for high-rises over twenty storeys on the former Premier Inn and Debenhams sites beside St James Barton roundabout; to replace the Galleries shopping centre on the northern edge of Castle Park; and over a recently installed heating network energy centre on the park’s southern side. Other major schemes on the horizon are Western Harbour, by the iconic Avon Gorge view of the suspension bridge, and Temple Quarter, one of the largest regeneration projects in the whole of Europe.

This all represents a profound challenge to Bristol’s historic character as a low to mid-rise city. The most vocal defender of that character has been the previous mayor Ferguson, an architect and former RIBA president, who first came to prominence in the city during the battles over the development of Bristol in the 1970s when he was a Liberal councillor. This was a previous period of disenchantment with the planning system documented in the 1980 book, The Fight for Bristol: Planning and the growth of public protest. It traces the reaction to the changes being imposed by the city planners during the decades following the Second World War. As in many towns and cities across Britain, this meant a wave of road-building, road-widening, modernist architecture, and the mass destruction of historic neighbourhoods. In Bristol there were also proposals to concrete over parts of the harbour and a boom in speculative office developments.

Central to the rise of resident and amenity groups in that period, together with concerned elements of the architectural profession, was the sense that the city’s unique history and identity were under attack. There was a powerful desire to protect what remained from going the way of other British cities with their increasingly generic and soulless appearance. An admirer of the human-scale form of European cities such as Amsterdam and Copenhagen, Ferguson has long championed a vision of the city that protects what remains of its architectural heritage and thinks about place-making in a holistic sense. This has included promoting policies to reinvigorate the docks, repurposing old buildings and keeping new high-rise office blocks away from the historic centre and segregated in particular areas such as Temple Quay, by the train station.

Possibly informed by his formative years living in North America as a young man, his successor has had a very different attitude. Throughout Rees’ time in office there has never been any sense that he has any personal enthusiasm for the architectural inheritance of Bristol. Similarly, arguments for the economic and social benefits of human-scale urbanism and its impact on quality of life and mental health, as well as tourism, have never been seriously addressed in his discussions about the city. In fact, there’s been a clear hostility towards Ferguson and his fellow campaigners, and an attempt to frame their criticisms as manifestations of “privilege”.

Something of this can be seen in a pointed exchange between the two men on Twitter in early 2022. Rees’ laconic responses appear to be insinuating a resistance on class and racial grounds to the idea of a shared inheritance of the city’s history and built environment, and Ferguson’s right to speak to it:

An earlier divergence from Ferguson’s vision of the city was a feature of arguably the most contentious single development issue of Rees’ whole time in office: the cancelling of long-held plans for a city centre arena. Bristol is the only core city without a major arena and a key policy of Ferguson’s mayoralty had been to use vacant publicly-owned land next to Temple Meads train station to get a project realised that had first been talked about as far back as 2003. In April 2016, a planning committee finally approved plans for a 12,000 capacity arena on the site, in what turned out to be Ferguson’s last month as mayor. Rees came into City Hall the following month promising to deliver the project, as he had done during the election campaign, but negotiations with the appointed contractor over costs had broken down by the end of the year.

Crucially, discussions with Bristol University had also been taking place during 2016 for the sale of a neighbouring tract of council-owned land, a former Post Office sorting depot, for a major new campus. This whole area had been designated as an Enterprise Zone by government in 2012 and the emerging ‘Temple Quarter’ project, which includes the upgrading of Temple Meads train station, and the regeneration of 130 hectares of brownfield land immediately to its south-east, is one of the biggest regeneration projects in Europe. This particular piece of land had been earmarked as the car park for the arena and its sale seems to have been the turning point when alternative options for the arena were explored in earnest.

The senior council officer overseeing the campus deal, Barra Mac Ruari, Strategic Director for Place, was also the council’s lead on the arena project. In April 2017, following the sale to the university in March, and as Rees made increasingly sceptical noises publicly about the arena scheme and commissioned a KPMG value-for-money report, YTL Developments UK - the UK arm of a Malaysian infrastructure conglomerate - contacted Mac Ruiari with an offer. Would he like to discuss the possibility of the arena being built instead at the former airfield they owned in Filton11. The idea had already been flagged to the Mayor, they said.

This land, on the city’s northern border with South Gloucestershire, had been bought from BAE Systems in 2015. The postwar Brabazon hangars, where Concorde was built, sit beside the disused runway in a nightmare Ballardian landscape, surrounded by car dealerships, new build estates, a giant shopping mall and sterile business parks containing some of the world’s largest weapons manufacturers. All overlaid with the constant white noise of the nearby A38 flyover and M5 motorway.

The following month, Mac Ruiari announced that he was leaving the council to take up a role as Chief Operating Officer with YTL and work on their project at Filton, which was already progressing as a large residential development, with or without an arena. Another senior Bristol City Council director, Robert Orrett - who’d also been working on the Temple arena project - then left in September and stepped in to the role of property director at YTL.12

Welcoming them into the fold was Colin Skellett, CEO of YTL UK, and also the long-time Chief Executive of the local water company, Wessex Water. Under the perverse logic of Britain’s privatised utilities, Wessex Water, which had previously been owned by the scandal-ridden US group Enron before it collapsed into bankruptcy, is now owned by the Malaysian property company. In fact, Skellett had been arrested in a dawn raid shortly after the takeover in 2002, suspected of receiving a near £1million bribe, but was later released without charge. An active figure in the region’s business circles, he had also been the chairman of the Local Enterprise Partnership when it had agreed to provide £53 million for Ferguson’s original arena scheme in 2014.

Another key turning point came in December 2017 when, following a trip to China where he was meeting with investors, YTL paid for Marvin Rees to fly on to Kuala Lumpur and put him up at the Ritz Carlton hotel. Meetings were had with YTL executives. Three days later, his recently installed Executive Director for Growth and Regeneration, Colin Molton, met with the pension fund asset manager and property investor Legal & General in London.13

They now had to deal with the ‘sequential test’, the stipulation in planning that prioritises city centre sites for major infrastructure rather than out-of-town ones. This meant that the Temple Island site needed to be offloaded and made unavailable if YTL’s plan at Filton was to progress. The deal that was ultimately struck - avoiding public procurement rules - was for Legal & General to get a 250-year lease on the site and build a conference centre, 345-room hotel, 550 apartments and two office blocks. Bristol City Council, as well as securing £32 million of public funds to prepare the land, agreed to guarantee rents on one of the office blocks for 40 years. Bristol University owns the northern portion of Temple Island and has outline planning permission for a 20-storey student accommodation block for its new ‘Enterprise Campus’, that will fuse lab research and business development, with a focus on new technologies.

In another twist, Mac Ruiari left YTL in May 2018 - once planning permission for the Brabazon development’s initial masterplan had been delivered - and went to work for Bristol University on the new campus, and he remains their Chief Property Officer.

Rees made much of a further report from KPMG (who were also YTL’s auditors) that specifically compared the merits of the two arena schemes, claiming that a private venture on the edge of the city was better for economic growth as well as making financial sense for the taxpayer. In September 2018 - against a background of loud protestations from sections of the public and opposition councillors - he formally approved the new plans for both sites, subject to planning consents. Since then, the arena has been used as the justification for improved transport connections to YTL’s Filton site, paid for from the public purse, including a new train station. This will now connect the ever-expanding Brabazon residential development, already coming to market, increasing its value, while construction work on the proposed arena - almost eight years after planning permission was granted for one in the city centre - is yet to begin.

This extraordinary stitch-up that played out across the first years of Rees’ administration established some of its core working principles. The Bristol business establishment had backed Ferguson for mayor - a public school former Merchant Venturer and, behind the colourful exterior, something of a shrewd businessman himself - but the arena saga showed that his successor was a man willing to take public flak to work for their interests and their vision of the city. There was a willingness to operate at the edges of probity, to get his hands dirty, to “get things done”.

This wasn’t lost on Sir Edward Lister, Boris Johnson’s notoriously compromised right-hand-man, and at that point, chairman of the government’s housing and regeneration agency Homes England - who were already providing funding for the Temple Quarter project. The Thatcherite former leader of Wandsworth council held directorships and consultancy roles with various development companies during the period he moved between the Deputy Mayor and planning brief at London’s City Hall; Homes England; and being Johnson’s chief of staff in Downing Street. One of these arrangements (£480,000 in fees between 2016 and 2019) was with the Malaysian property developer EcoWorld, with whom Rees had also met with while on his YTL-paid trip to Kuala Lumpur.

Lister’s public backing for the arena decision had been eagerly sought by Rees during 2018 and the mayor personally sent a pre-written statement for Lister to pass off as his own, praising the approach taken. The text released in July 2018, and reported on by the Bristol Post, was an edited version. Some of its lines - whoever wrote them - had the ring of truth:

“We see evidence of a commitment to the pace and scale of delivery that is winning the interest of Government and the private sector alike…Bristol is at a pivotal moment where impending decisions will affect the City’s future for generations to come.”

St Mary le Port

In order to better understand the forces that are shaping the current and future development of Bristol, this investigation looks in detail at how the planning process for a single major development in the historic centre of the city unfolded. This is the imminent office-led scheme at St Mary le Port that was first approved by Bristol City Council’s Development Control Committee A in December 2021. Following an unsuccessful request from the Bristol Civic Society for the government to ‘call-in’ the decision and refer it to a public inquiry, it was finally granted planning permission in September 2022.

Well over a year has passed since permission was granted but still no demolition or construction work has started on site. I’ve been told by a council source that a potential anchor office tenant pulled out, which may have delayed plans, though the planning permission also specified a long list of pre-commencement conditions that had to be fulfilled. High inflation and construction costs mean the investors and developers may have also been waiting for market conditions to improve before making a start.

Despite the move to home-working, demand for Grade A office space is still deemed to be strong in Bristol and rents are high - the highest of the UK’s “Big 6” regional office markets in 2022. A recent report by CBRE identified Manchester and Bristol as the UK’s highest growth cities across multiple real estate sectors over the next ten years. And when I spoke to the PR company representing the developer in late November 2023, I was told that work would be beginning on site in early 2024.

Using Freedom of Information requests and other sources of evidence in the public domain, this investigation looks in detail at how the St Mary le Port planning process unfolded. As the city becomes increasingly transfigured by bland high-rise blocks, contrived ‘quarters’ and privately-owned pseudo ‘public’ space, this is an attempt to lift up the bonnet and look at how the mechanics of its planning and development regime has actually been working; to get a sense of some of the key actors involved, the relationship between developers and the local authority, and the professional networks that are creating the new city.

It reveals a variety of troubling aspects around this particular scheme: design and heritage specialists being sidelined within the council; political interference from the Mayor’s Office; apparent pressure on senior officers in the planning department to back proposals they don’t believe to be policy compliant; those officers misleading councillors on a planning committee; as well as bogus community representation. It also exposes some of the unhealthily close relationships between local politicians, the development industry, PR firms and the local media.

St Mary le Port is where Bristol began, more than a millennium ago, and was at the beating heart of the city from the Middle Ages to the Twentieth Century. The area suffered brutal destruction from Nazi bombs and then had to endure further indignities at the hands of post-war planners and architects. The way in which the decision was reached for such an important and sensitive site in the city - and the wider context in which that decision was made - is worth reflecting on.

An Ancient Place

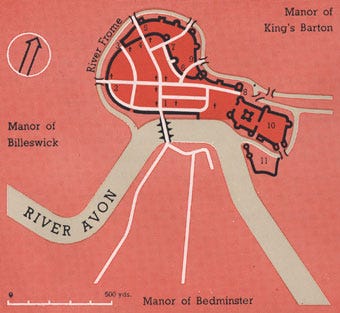

The precise dating of Bristol’s origins is contested but the ridge of high ground between the river Avon and its tributary the Frome, where the city began, was undoubtedly settled in late Saxon times. Coins were being minted on the site from at least as early as the 1020s – sign of an established market town. Here was a crossing point of the Avon that also provided safe harbourage, ideal for inland trade routes as well as offering good access across the sea to Wales, Ireland and beyond.14 The crossing gave the settlement its original Saxon name, Brycgstow: the place by the bridge. The loop of waters surrounding on three sides made it a highly secure and defensible location.

Before the Normans built a castle on the eastern land approach of this favourable peninsula, the crossroads known today as High Street, Broad Street, Corn Street and Wine Street was already established at the core of the town. The timber Saxon bridge lay just to the south, most likely on the site of today’s Bristol Bridge. This layout may have first developed as one of Alfred the Great’s burhs, the defensive settlements that he and his descendants built to repel Viking attack, as well as to create market towns and administrative centres. It was after all a strategically important site on the border of the kingdoms of Wessex and Mercia, well-placed for commerce, and on a river that the enemy’s longboats would be likely to glide up. Perhaps it was Alfred’s formidable daughter Aethelflaed, Lady of the Mercians, ruler of this place in the early 10th century following the death of her husband, who first gave the order for the grid layout of the new town.

The four streets mark out the ancient divisions of the borough: the parishes of St Mary le Port, Holy Trinity (later Christ Church), St Ewen's, and All Saints. St Peter's, a later iteration now standing as a ruin in Castle Park, is generally thought to be the earliest church, but didn’t lie within the borough. It was the parish church of the royal manor of Barton Regis, which Bristol became part of, and the church was absorbed into the town as the building of the castle extended its boundaries beyond the early Saxon fortifications.

St Mary le Port, 150 metres to the west, has a fair claim to be the site of the first church of Bristol. Archaeological excavations in the 1960s revealed that the lost thoroughfare of Mary le Port street, immediately to the north of the church, ran along a Saxon hollow-way. The building historian Jean Manco has even suggested that the church’s origins may lie with a royal fort established by King Offa of Mercia, as far back as the late 8th century:

“An almost circular mid-Saxon fort could have been enlarged to take in St Mary-le-Port, which might explain why this church was not aligned with the street frontage. By contrast the churches of St Werburgh, All Saints, Christ Church and St Ewens respect the street lines of the late Saxon burgh. They are all placed prominently on or near cross-roads and were probably founded early in the process of settlement.”15

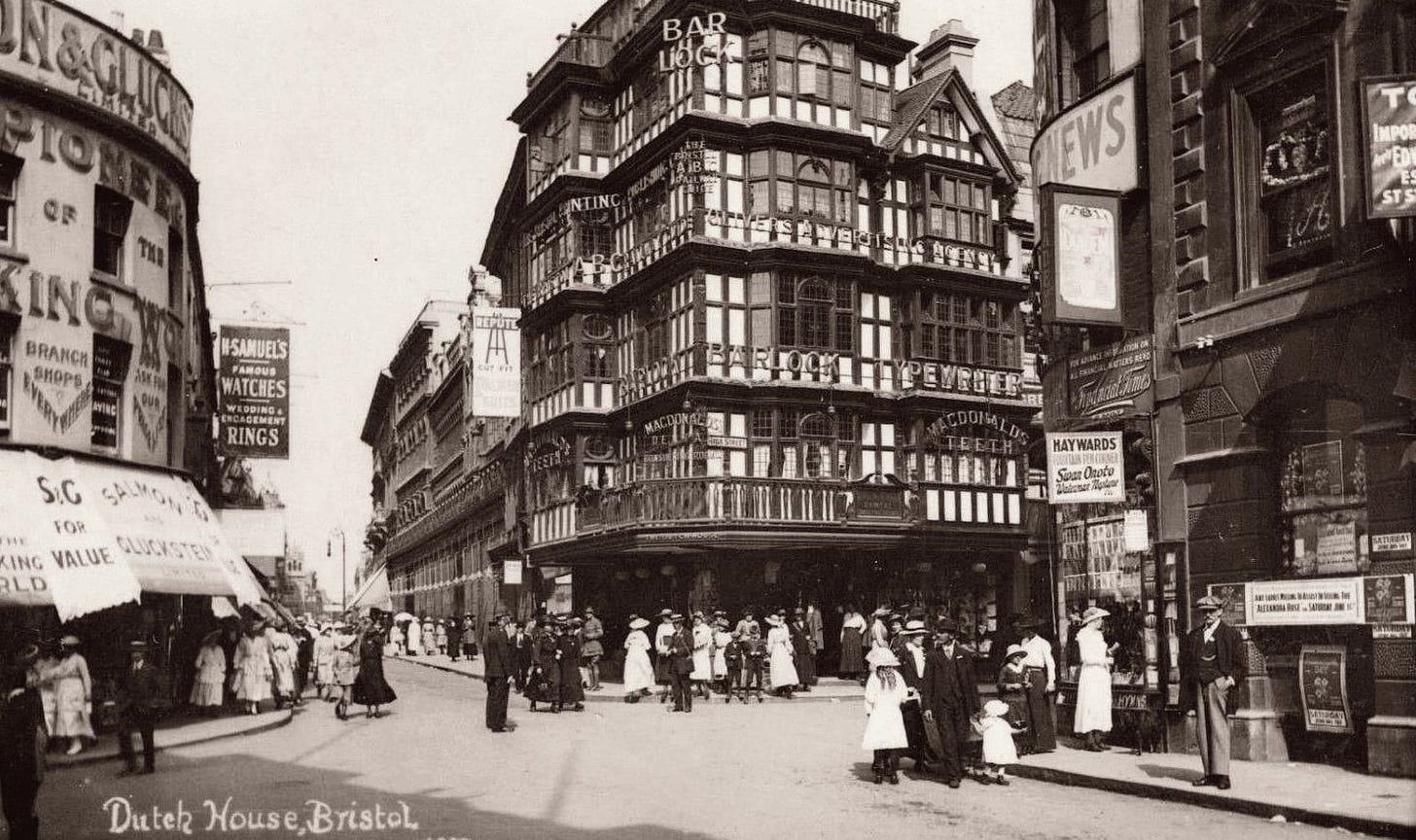

Until the 15th century, the church was referred to in documents as “Blessed Mary” or “St Mary in Foro”, reflecting close proximity to the town’s market (forum in Latin), rather than to the docks, as the later mutation of the name to “Port” suggests.16 A monumental market cross, Bristol’s High Cross, stood at the crossroads from the early 15th century to the 18th, and a cross of stone or wood is thought to have stood there since Saxon times.

The Second World War brought terrible destruction to this ancient place. On the evening of 24 November 1940, a bombing raid by the German air force destroyed much of the historic centre of Bristol, which had become the city’s bustling shopping and entertainment district. In a few hours, many of the tightly packed streets and alleys, with their half-timbered late medieval buildings, were reduced to rubble and charred embers. And most of what remained standing would soon be pulled down. This included Castle Street, running in from the west of today’s park to St Peter’s church, that would be humming with life on a Saturday night, filled with huge numbers of Bristolians out for a good time. This was a place of pubs, cafes, hotels and cinemas, as well as shops, homes and churches.

But as the Lord Mayor at the time, Thomas Underdown, said: “The City of Churches had in one night become the city of ruins.” Both St Peter’s and St Mary le Port were badly damaged, their roofs lost. The famous 17th century timber-framed ‘Dutch House’, on the corner of Wine Street and High Street, was destroyed by fire from incendiary bombs. And the human cost of this and later attacks was immense. During the ‘Bristol Blitz’ between November 1940 and April 1941, there were six bombing raids that resulted in 1,299 people being killed and 1,303 seriously injured.

After the bombs came the reconstruction. It's a well-worn trope in Bristol that the post-war planners did more damage to the city then the Luftwaffe. While some of that post-war transformation was motivated by a genuine and admirable desire to improve people’s living conditions - and was constrained by a lack of money, of course - today the city has to live with the terrible planning decisions inflicted on it by architects, developers and the city council.

Together all these destructive forces, from home and abroad, succeeded in obliterating huge swathes of the extraordinary city that J.B. Priestley had marvelled at in the 1930s17. In its place we have the anti-human grimness of St James Barton, Lewin’s Mead, Broadmead shopping centre, and the exiling of faded Old Market Street to the outer dark beyond the Temple Way Underpass. So much of central Bristol is marked by twentieth century place-making failure. For all its surviving charms, to walk around the city centre with this knowledge is to feel a powerful sense of loss and maltreatment. Nowhere more so than the current site at St Mary le Port, with its drab 1960s and 1970s office buildings wrapped around the remains of the medieval church.

The significance of this particular site is also rooted in the fact that for much of the medieval and early modern period it was the heart of England’s most powerful and influential city after London, often referred to as the country’s ‘Second City’. For good and ill, Bristol’s status as a global trading port, the role it played in the Plantagenet dynasty taking the English throne, John Cabot’s ‘discovery’ of America and its later colonisation, Methodism and the dissenting tradition, as the birthplace of English Romanticism, for the evil involvement in the Atlantic slave trade, for Brunel’s engineering and much else besides, all combine to make its origin, at the historic centre of the city, a site of national and international importance.

But perhaps most significant of all are the innumerable and unmarked human lives that have passed through this place over the course of more than a thousand years of continual settlement. This makes the historic heart of Bristol, to my mind, not just an ancient place but a sacred one. While clearly subject to the commercial demands of a prominent city centre location, it is a site that you would expect the city authorities to treat, at the very minimum, with a robust sense of diligence, care and respect.

The Site

The 1.15 hectare site permitted for development sits on the north-western corner of Castle Park and is bordered by High Street to the west, sloping down to Bristol Bridge, and Wine Street to the north. The three empty and largely derelict former office buildings that currently stand there, surrounding the church tower on three sides, are Norwich Union House, Bank House and Bank of England House. The site is located in the City and Queens Square Conservation Area.

All that remains of the church from the destruction of November 1940 is the 15th century tower - with its three corner pinnacles and a crocketed spirelet above the stair-turret, in the local style – plus low-standing fragments of the church walls. Surrounded by the concrete facades of the abandoned and graffitied buildings, with their windows boarded up, the church tower stands out of public reach behind a fence and is on Historic England’s ‘Heritage at Risk Register’. The abandonment of the buildings has created a shabby, half-hidden zone at the edge of the park. The buildings have been squatted at various times and there was a fire at Bank of England House in 2017. Though the Twentieth Century Society have made efforts to spare the buildings from the bulldozers, very few people have suggested that the site isn’t in need of demolition and redevelopment.

Directly to the west, on the other side of High Street, is what remains of the Old City and its dense concentration of Georgian and Victorian listed buildings. As you currently look across the site from Castle Park you see the grouping of historic churches, with the spires and towers of St Nicholas, All Saints, Christ Church St Ewen and St Mary le Port forming a distinctive skyline, still visible from vantage points across the city.

The site has a chequered and contested post-war history. In 1947, as plans for reconstruction were taking shape, a public referendum organised by traders voted overwhelmingly (13,363 to 418) to rebuild the heart of the shopping district around Castle Street, Wine Street and Mary le Port Street rather than move it to a new site at Broadmead.18 The council’s planning committee, swayed by the big national retailers, ignored the result. Instead, the area was used as a temporary car park with land on the western side being leased to the Bank of England and Norwich Union Insurance Company for office buildings built in 1962 and 1963.

There was a large public protest at the time opposing the Norwich Union Building, with a petition receiving over 11,000 signatures.19 Again it was ignored. In the mid-1970s, an additional building, Bank House, was built alongside Bank of England House. And in 1978, Castle Park finally opened directly to the east of the site, with long-held plans for a series of civic buildings, including a new museum and art gallery, abandoned.

Bristol City Council maintained the freehold of the buildings through the entirety of the site’s operational use. Norwich Union and the Bank of England vacated their buildings in the 1990s but attempts to redevelop the site this century have floundered. In 2006, council leaders blocked a £150 million scheme proposed by architects Aukett Fitzroy Robinson because of its impact on Castle Park. Instead, the council selected Deeley Freed as its preferred developer for the site. They proposed a mix of apartments, shops, cafes and offices.

In response there was an attempt to register Castle Park as a ‘Town or Village Green’ by the newly-formed community group ‘Castle Park Users Group’, in order to see off this development proposal. This went to a public inquiry and though the attempt was unsuccessful, the wider public reaction and the delay created - which pushed things into the period of the global financial crash and a consequent squeeze on construction - meant these proposals were eventually withdrawn. In 2013, the ‘Castle Park Users Group’ re-formed to successfully oppose a site allocation in the draft Bristol Central Area Plan that they felt encroached on the park.

Lloyds Banking Group continued to operate in Bank House before finally moving staff into their main headquarters on the harbourside in October 2020. At the same time as Lloyds closed their operations in Bank House it was announced that, for the first time, the three leaseholds were under single ownership and development proposals would be coming forward. The US-based global investment manager Federated Hermes had bought up all three buildings on the site between October 2018 and February 2020.20

Federated Hermes, BT Pension Scheme, MEPC

Federated Hermes is a global investment manager with around $700 billion worth of assets under its control at the time of writing. It makes money by providing investment opportunities in equities, credit, infrastructure, private equity, private debt and real estate. In 2022 it made an annual profit of $239 million. It came into being in 2018, when Federated Investors – an investment manager founded in Pittsburgh in the 1950s - completed its acquisition of a 60 percent interest in Hermes Investment Management, a London-based entity set up during the financial deregulation of the 1980s to manage the newly privatised British Telecom Pension Scheme (BTPS).

The biggest two shareholders in Federated Hermes are The Vanguard Group and BlackRock, with 10.10% and 8.58% stakes respectively at the time of writing.21 These are the two giant investment firms of corporate America and the largest in the entire world. Between them they have almost $20 trillion of assets under management, across a wide array of global industries including the largest stakes in the biggest companies in media, oil and gas, pharmaceuticals, Big Tech, banking and weapons manufacturing.

BTPS is the biggest corporate pension scheme in the UK and one of the largest in Europe, with, until recently, assets of around £57 billion (they lost about £10 billion of that during the market turmoil following Kwasi Kwarteng’s infamous ‘mini-budget’ in September 2022). Around 9% of its assets were invested in property in 2022. It’s a mature pension scheme that closed to new members in 2001, with an average member age of 68. By 2034 almost all of its 270,000 members will be retired.22

The purchase of the three leaseholds at St Mary le Port and the planned redevelopment of the site has been carried out by Federated Hermes in conjunction with BTPS as the investor, with whom they have a longstanding and interwoven commercial relationship. In May 2022, Hermes GPE (a wholly owned subsidiary of Federated Hermes) was awarded a $1 billion private equity mandate by BTPS called ‘Horizon III’, the third $1 billion deal between the two since 2015.

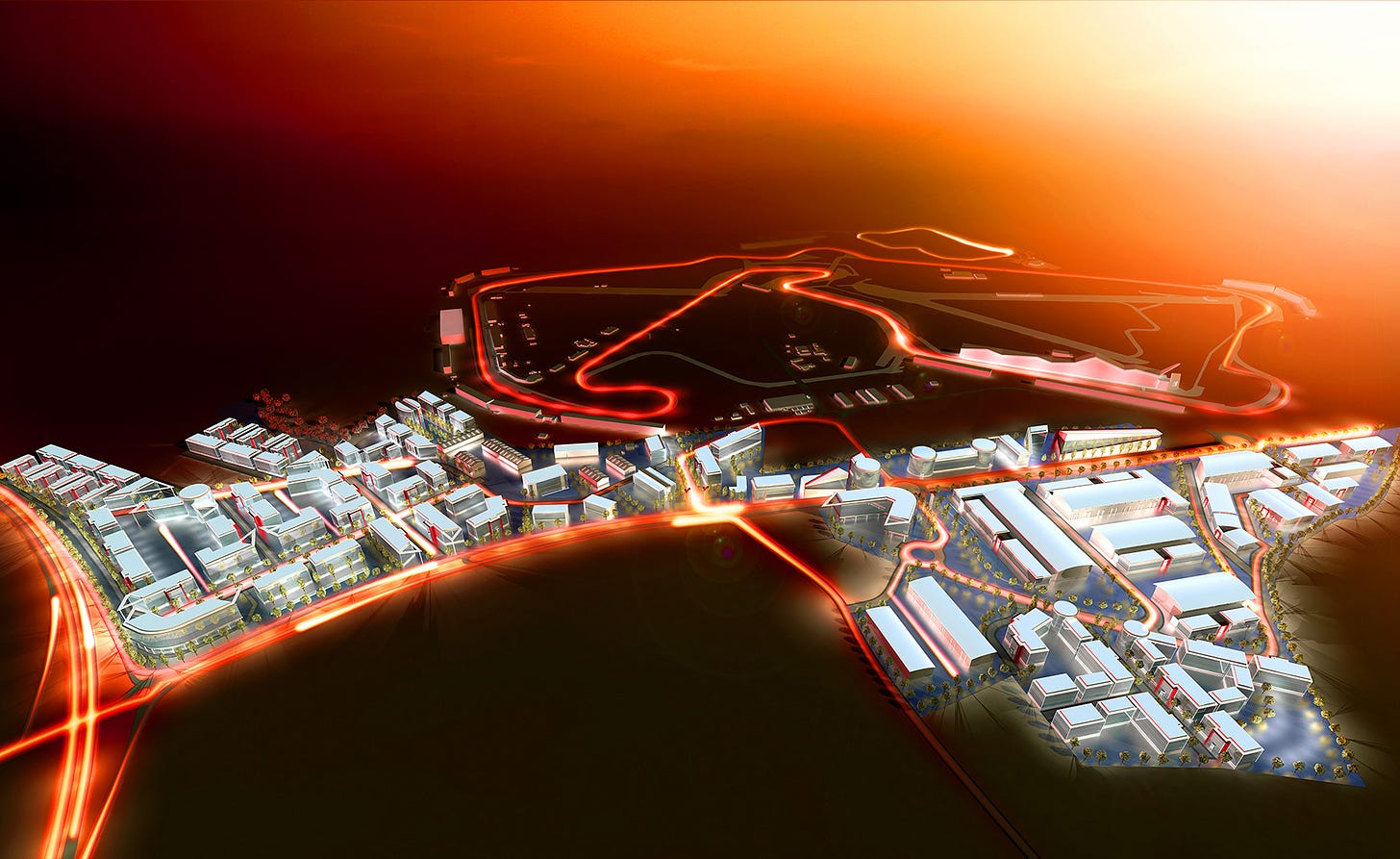

With BTPS as the investor and Federated Hermes (previously Hermes GPE) as the manager of their money, several very large commercial developments have been built in the UK over recent years. These include Silverstone Park, a 130-acre technology and research business park next to Silverstone Circuit in Northamptonshire; office blocks for Paradise Birmingham, a £1.2 billion regeneration scheme in the civic centre of the city; Milton Park, a 250-acre technology and business park in Oxfordshire; NOMA in north Manchester, a mixed-use residential, business and entertainment development that is currently the largest regeneration project in the North West of England; and Wellington Place, an office-led scheme that included the biggest ever office pre-let in Leeds’ history.

For all these developments – and for St Mary le Port in Bristol – MEPC has been the developer and ongoing manager of the sites themselves. They are also now a wholly owned subsidiary of Federated Hermes, having been bought in January 2020 – from the BT Pension Scheme.

So to be clear: for this development we have Federated Hermes (investment manager and leaseholder of the site), the BT Pension Scheme (investor), and MEPC (developer and site manager, owned by Federated Hermes). The applicant for planning permission was ‘SMLP BRISTOL GP’, a joint venture General Partnership incorporated on 12 September 2018 and registered at Federated Hermes’ offices in the City of London. As with most major developments in Bristol, Savills acted as an agent and conducted much of the formal pre-application correspondence with the council.

Roz Bird: Commercial Director

With vacant possession of the site’s final building imminent, in August 2020, MEPC’s Roz Bird was brought in to oversee the planning application process. Since 2014, Bird had been Commercial Director at Silverstone Park in Northamptonshire, running MEPC’s expanding development of the high-performance technology park (advanced engineering, electronics and software development), that sits next door to the famous motor racing circuit.

She had also become the leading voice advocating for the area around Silverstone Park to be recognised as a ‘technology cluster’ within the emerging region of high-value science and technology companies identified by government and business as the ‘Oxford to Cambridge Arc’.

From 2016 she was Chair of the newly formed ‘Silverstone Technology Cluster’. The membership page on its website offers a description:

“Silverstone Technology Cluster (STC) was founded to help companies in and around Silverstone make money, increase their profits and grow. STC is an integral part of the Oxford – Milton Keynes – Cambridge Super Cluster and, through our members, we increase the value of the local economy.

Join our community to meet like-minded people and be part of a critical mass of high-tech and business activity in the local area which attracts the attention of government, the finance community and large corporates.”

In a 2021 interview, Bird reflected on her time as Chair of STC: “When we’re thinking about our brand essence, and what we exist for, it is about creating a sense of ‘community’ – for the companies to feel part of something where the whole is greater than the sum of its parts; where they can get inspiration from each other and where there’s a chance to collaborate and win new business.”23

Architects of ‘Paradise’

The architects appointed by MEPC to design the St Mary le Port scheme were Feilden Clegg Bradley Studios (FCBS). Established in Bath in the late 1970s, they’ve picked up a large number of RIBA awards over recent decades for what the firm describes as “sustainable, democratic, and socially responsible design.”24 Early pioneers of green, energy-efficient buildings, with an affinity for the Arts and Craft movement, they have developed into a much larger and more conventional practice, but one well-placed to capitalise on the current corporate focus on Net Zero and sustainability. While working across the UK, FCBS have been involved with some of the most significant developments in Bristol in recent years, all strongly supported by the current mayoral administration. They have designed buildings for Bristol University’s Temple Quarter Enterprise Campus, the residential scheme for YTL that forms part of their Brabazon development at Filton and the ill-fated ‘Boatyard’ apartments on Bath Road.25

While they were completing work on the design of St Mary le Port in late 2020, they also won a competition to work with Federated Hermes and MEPC on a 10-storey office block at Three Chamberlain Square in Birmingham, part of the huge ‘Paradise’ regeneration development in the city centre. Grant Associates, the company working on the landscaping and so-called ‘public realm’ for the St Mary le Port scheme, are also working on Three Chamberlain Square.

Plans for the scheme inspired the memorable headline in the Birmingham Mail: “'Big brown turd' that will tower over Birmingham town hall leaves residents unhappy”. Construction is currently underway after it was approved unanimously by councillors in June 2022.

As at St Mary le Port, the council is the freeholder of the land, but here large amounts of funding from the public sector has also facilitated the wider regeneration project. Located within the Birmingham City Centre Enterprise Zone, Paradise Circus Limited Partnership (PCLP) was established as a joint venture between Birmingham City Council and the BT Pension Scheme (managed by Hermes) to deliver much of the project, which includes ten new office buildings, a hotel, shops and restaurants.

Funding was received at the outset from the Greater Birmingham and Solihull Local Enterprise Partnership to the tune of £87.79m for demolition and infrastructure works prior to construction. This was to be spent over three phases. However, in 2018 it was revealed that all the money had gone after phase one. Other than abandoning the project, the local authority had little option but to accept the developer’s demand for more money. And in January 2019 a further £51.28m million was taken by Birmingham City Council from the Local Enterprise Partnership for the scheme, to facilitate phase two of public realm, demolition, infrastructure work and costs associated with the liquidation of the previous contractor Carillion. This is money the council has to pay back from business rates, which they are now projected to be doing until the mid-2040s. Meanwhile, the council has ceased all non-essential spending on services after declaring itself bankrupt in September 2023.

Before returning to St Mary le Port it’s worth noting that the planning and development consultancy Turley worked with MEPC to deliver the planning applications for phase two of ‘Paradise’, including Three Chamberlain Square. The current Labour Bristol City councillor Marley Bennett is now employed as a consultant by Turley. Bennett sits on the council’s Growth and Regeneration Scrutiny committee, directly concerned with planning-related matters, and was also recently made a Cabinet member by Marvin Rees, taking the portfolio for Climate, Ecology and Waste. He also sat on the planning committee that deliberated on the St Mary le Port application and personally voted to approve it. While that happened prior to his employment with Turley, it illustrates the interwoven relationships of these development companies, as well as the inevitable conflict of interests of local politicians who are in their pay.

Making Plans

According to MEPC’s planning statement, submitted as part of their planning application, an interest in the site was first expressed by Federated Hermes in response to the council’s ‘Call for Sites’ exercise undertaken in March 2017. This was the start of the review of the Local Development Plan instigated by Rees’ administration and called for developers with aspirations for sites within the city to make their representations.

MEPC’s Design and Access Statement - which formed part of their planning application and contains a timeline of the scheme’s evolution - states that the St Mary le Port design work began in March 2019. This was around five months after Federated Hermes had bought the leaseholds of the first two buildings and six months after ‘Bristol SMLP GP’, the joint venture General Partnership that would ultimately apply for planning permission, was incorporated. The final building, Bank House, was purchased in February 2020.

A draft Planning Performance Agreement (PPA) - a framework agreed between the LPA and the applicant about the process for considering a major development proposal - had evidently been worked on by both parties in 2019. And on 6 April 2020, following a period when land ownership and site acquisition negotiations were going on - and at the end of the second week of the first Covid-19 lockdown - Savills emailed the two most senior officers in the council’s planning department, Zoe Wilcox and Gary Collins, stating their client’s desire to move forward with development plans.

Dear Zoe and Gary,

I hope you are well and keeping safe in these challenging times.

It is a little while since we were last in contact regarding St Mary le Port, but I am sure you will be aware that there has been a focus on site acquisition which will allow a comprehensive approach to be adopted.

We are now keen to move forward again into engagement with the regulatory teams and this is really a courtesy email to highlight this.

We made good progress last year on a draft PPA. I have updated this and will send to Gary. The differences from the previous version are in terms of process (we will proceed as EIA development) and in terms of a target programme.

We had discussed the likely quantum of resource payment last year. Hopefully we can get to a settled PPA relatively soon.

In terms of a “catch up” on the scheme then we would like to diarise this in week beginning 11th May if it is possible for Gary to coordinate with colleagues in planning, urban design and transport. We can organise via a video conference facility and agree the format closer to the time. I am very grateful for your cooperation and I fully recognise the difficulties which planning departments are experiencing.

I look forward to working with your teams on this important site, and I know that Hermes Federated (as investor/leaseholder) and MEPC (as development managers) are very enthusiastic about the opportunity.

Please don’t hesitate to contact me if you have any questions.26

Gary Collins, Head of Development Management, replied:

Thank you for your e‐mail.

It is good news that the wider site is being assembled and that your clients are keen to progress the scheme.

We are very keen to keep the development pipeline flowing and are happy to meet up via video conference.

I’ll coordinate the colleagues that you mention and will come back to you with availability during w/c 11th May.

Regards

Gary

On the 23 April, an ‘Introduction Meeting’ took place between Federated Hermes/MEPC and the council’s Executive Director for Growth and Regeneration, Stephen Peacock and Director of Economy of Place, Nuala Gallagher. This had been scheduled back in February as an in-person meeting at City Hall, but with the onset of the pandemic, it was done online.27

The meeting in May with the planning department did happen according to MEPC’s planning application documents. And there were also two meetings with Historic England over the summer. Historic England is an executive non-departmental public body of the government, that as well as generally championing historic buildings and places, has a statutory role in the planning system. Local authorities must consult them and consider their advice when assessing planning applications that might impact designated heritage assets or their setting.

According to the Title Register of Bank House, a deed of variation on the leasehold agreement was signed between Bristol City Council and Federated Hermes on 24 June 2020, with “the benefit of the legal easements granted…for a term of years expiring on 19 October 2163”.

On 25 August, Bristol City Council entered into a contract with CBRE, the commercial real estate services and investments firm, for £22,500. According to the council’s list of published tenders for that quarter:

“The purpose of this brief is to appoint an external consultant with the expertise and experience to support the Council in bringing forward this important site. The external consultant needs to bring ideas and commercial expertise to ensure the agreement with Hermes maximises revenue returns to the Council and benefits to the City.”

The first official ‘Pre-Application 1’ meeting between representatives of Federated Hermes and Bristol City Council planning officers took place on 27 August 2020. And on 14 September there was a Bristol City Council online Cabinet Member briefing, with a presentation given to councillors by representatives from Federated Hermes and Savills.

After Federated Hermes took control of the final building from Lloyds on 9th October, Roz Bird met with the council’s Executive Director of Growth and Regeneration, Stephen Peacock, and the Head of Regeneration, Abigail Stratford, at the site on 13th October. Bird wrote to them afterwards:

“It was great to meet you both on site today. Thank you for your time and for a good initial discussion about the potential issues and opportunities on the site.

As you know, we’re working on plans for pre app 2 at the moment, which I believe is set for early November, and we’re also sending out a press release, with a link to a SMLP website, this week.

As suggested, it would be good to have short catch‐ups throughout the process to ‘check in’ and confer on the design as it progresses.

Our intention is to bring forward an exciting, policy compliant scheme, with clear references to key stakeholder feedback, in order to provide a place that works well with the surrounding activities and breathes life in to the site.

I look forward to working with you both. Please do not hesitate to contact me with further thoughts, and questions, as they arise.”

MEPC and Bristol City Council put out a joint press release later that month, covered by local media outlets. Roz Bird was quoted as saying:

“The site has huge potential, and with the acquisition of all three buildings complete, and control of the site under one ownership for the first time in decades, we are now in the position to take forward proposals to transform this historic location.

We will work in partnership with the public sector, and local communities, in order to create a great place - combining heritage, culture, education and commerce – which will provide sustainable financial returns and positive societal and environmental outcomes.

We are extremely sensitive about the responsibility for redeveloping such a pivotal and historic site in the centre of Bristol and have therefore appointed Feilden Clegg Bradley, as our lead architects, given their expertise. We are excited about what is possible at St Mary le Port.”

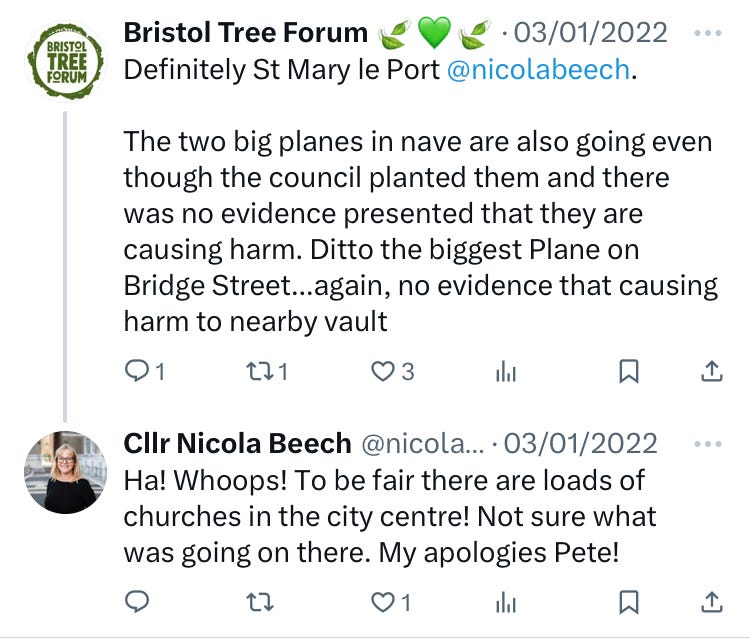

Labour councillor Nicola Beech, Cabinet member with responsibility for Spatial Planning and City Design, was also quoted in the press release:

"I am really pleased to see the acquisition of these three buildings.

I look forward to working with Federated Hermes and MEPC to deliver a high quality redevelopment of the site, with a focus on transport improvements and excellent areas of public realm.

We will be working closely with MEPC to ensure that St Mary le Port has a much brighter future.”

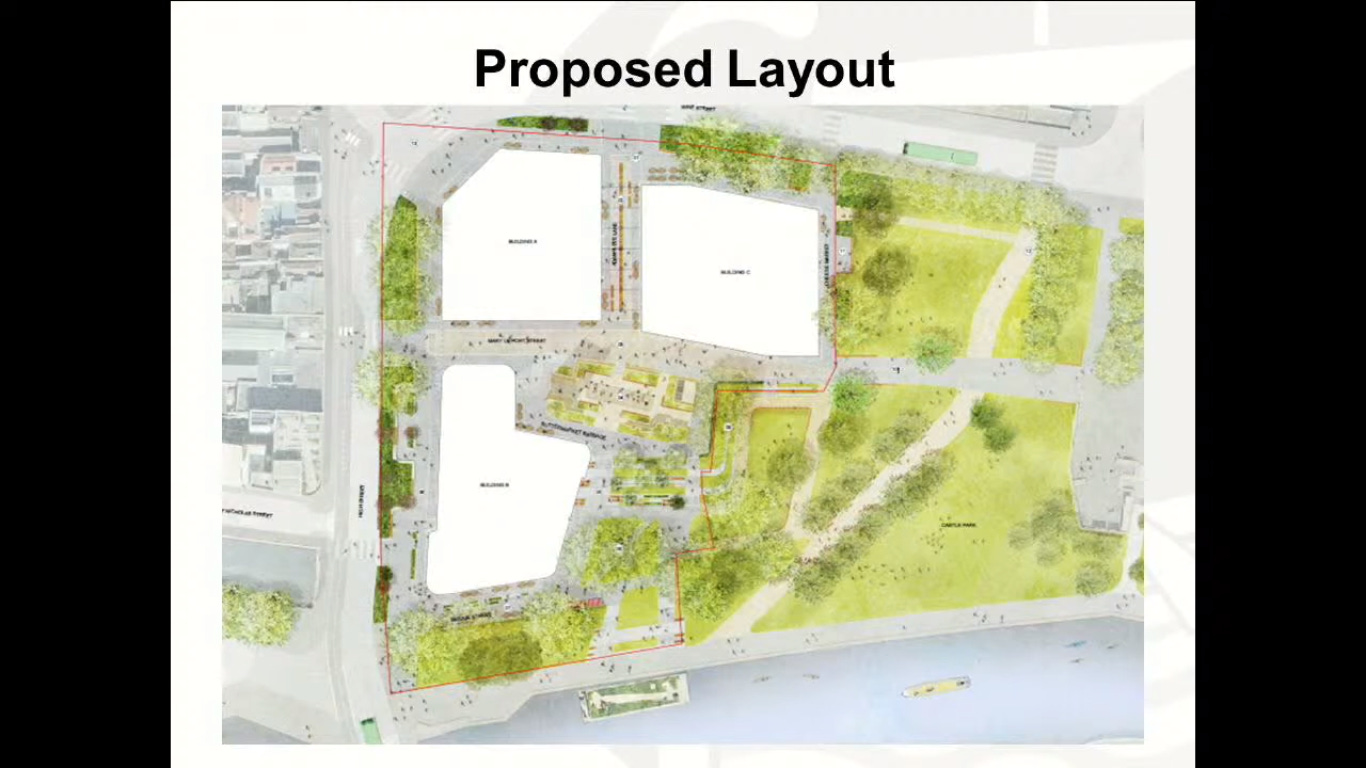

Though no designs for the scheme were unveiled publicly with this press release, the essential shape of the scheme was already established. By February 2020 it had been decided that the scheme would be three blocks, echoing the layout of the existing buildings rather than four blocks forming a square, as initially worked on. This is from MEPC’s planning application:

“Further land dealings had influence over the areas selected for development. The masterplan was then adjusted to only include 3 building plots all sitting within the development boundary line and not building into the park…3 buildings plots were established and giving the 4th quarter back to Castle Park and retaining trees, was the approach the Applicant felt was the most appropriate for this significant Site and for Bristol, but with this adjustment the mass that previously sat in the 4th quarter needed to be redistributed across the 3 buildings to ensure viability of the development.”28

In the days following the press release, an MEPC employee - I assume Roz Bird herself as the address on the emails is Silverstone Park - can be seen in correspondence released through this FOI request, trying to set up a meeting with parks officers. They respond saying that they are working through an internal council process so can’t meet. Bird then writes to Nicola Beech in frustration on 23 October:

“Hi Nicola,

Please see the email string below.

As we discussed, when we were on site, I have tried to arrange a meeting with [REDACTED] but to no avail. Please see email string below, anything you can do?

I have also emailed [REDACTED] but have not heard back from him, I’m guessing this is also stuck?

I think we all want the same thing - a great new development on the site - but maybe there is a difference of opinion about how we go about it?

As there are so many detailed conversations to have, on so many fronts, I need to meet with individual specialists, on their topic, and focus on their issues one by one, so full understanding is gained and the ‘puzzle pieces’ can be brought together. Meeting up as one homogenous group to talk at a pre app meeting, for the first time, won’t get the job done.

I hope that makes sense, and again, apologies for bothering you with this.

Kind regards

Beech forwards to Stephen Peacock:

Hi Stephen

Here we go again. I’ll go back politely but I have to say this playing off each other is really frustrating.

Nic

Peacock replies:

I’ll send you a note I just sent her - you were next on my list!

Proposals

The design proposals were made public for the first time by MEPC on 8 April 2021, as they announced a ‘public consultation’ on the plans, which were reported on in the local media. Two public online presentations took place on 21 and 22 April 2021.

It can be seen from the notes for Pre-Application Meeting 4, which took place 11 March, that MEPC were at this point already fixed on a May submission for their planning application – just a few weeks after the planned consultation meetings:

“Consultation next month

Appln due 1st half of May”

This was clearly always going to be far too short a timeframe for any feedback to have any meaningful impact on the proposals. And the window for consultation was only open for 18 days, until 26 April. In the end, there was just five weeks in between these public presentations and the submission of the application on 28 May.

The scheme they were revealing was for three very large new office buildings with retail or food and drink premises at ground floor level. The office blocks consisted of one nine-storey building and two eight-storey buildings, with their commercial floor dimensions making them substantially taller than if they had been residential buildings with the same number of storeys.

Other elements to the plans included alterations and repairs to the church tower and ruins as well as the High Street Vaults - medieval wine cellars that lie beneath the site and have Scheduled Monument status. There was hard and soft landscaping and new ‘public realm’, as well as the re-establishment of three street lines lost during the Bristol Blitz: Adam and Eve Lane, Cheese Market and part of Mary le Port Street.

What is immediately striking about the buildings is their jarring and dissonant appearance within the context of the Old City. They have a domineering presence, with their great height relative to their surroundings and their squat proportions. The three buildings seem to have little cohesive identity, with each one going off in a very different referential direction. While the materials and design make various claims of local distinctiveness, the overriding commercial demands, coupled with the bland styling of contemporary architecture, mean that they could have been dropped in from anywhere in the world.

Block A, on the High Cross corner of the crossroads, takes its jettying structure from the lost Dutch House. But the parodic office block is not fooling anyone that it’s doing anything other than maximising returns on floorspace.

Block B, to the south, has been given a terracotta colour that is supposed to be a reference to the historic brick warehouses along Redcliffe Wharf across the floating harbour, as well as nodding to the Bristol Byzantine style. But Redcliffe is an entirely different conservation area, with a very different history, grain and appearance to the Old City immediately across High Street. The building jetties out here too, giving it a domineering presence. The building also looms over the southern side of the church tower, claustrophobically close. At the top, a discordant jumble of terraces produces a strangely unbalanced view from Bristol Bridge.

Block C, the tallest of the buildings, sits closest to the park and presents a sheer cliff face to it.

The lost Old City was densely packed, but buildings of twice the height create a completely different, bullying effect. The busy vertical grids on the buildings are an attempt to mitigate their bulky form but the Bristol building they’re most reminiscent of perhaps is the modern Bristol Royal Infirmary hospital.

And as we’ll see, the plans being made public had been subject to severe criticism from specialist officers within the council for many months, and this was unresolved and still ongoing.

Planning Policy Context

When Marvin Rees became mayor in 2016, the local development plan in Bristol had been a framework of documents made up of a Core Strategy, adopted in 2011, Site Allocations and Development Management Policies, adopted in 2014, and the Central Area Plan, adopted 2015. A variety of supplementary planning documents and other planning guidance also existed to inform decisions.

As previously mentioned, although much of this framework had been approved by the council relatively recently, an early priority of Rees’ administration was to review the local plan with a view to replacing it with a new one. And a primary motivation for this was to encourage an increase in densification - largely seen as being achieved through tall buildings.29

Adopting a new local plan is a laborious and time-consuming process; so time-consuming that Bristol’s new local plan will only come into effect after Rees’s departure. Delayed by a failed West of England Spatial Plan that tried to establish new housing provision across the region’s local authorities under a single regime, consultation for a Bristol-only local plan began in 2019. The full document has only recently been approved by Full Council and it now needs government approval before coming into force.

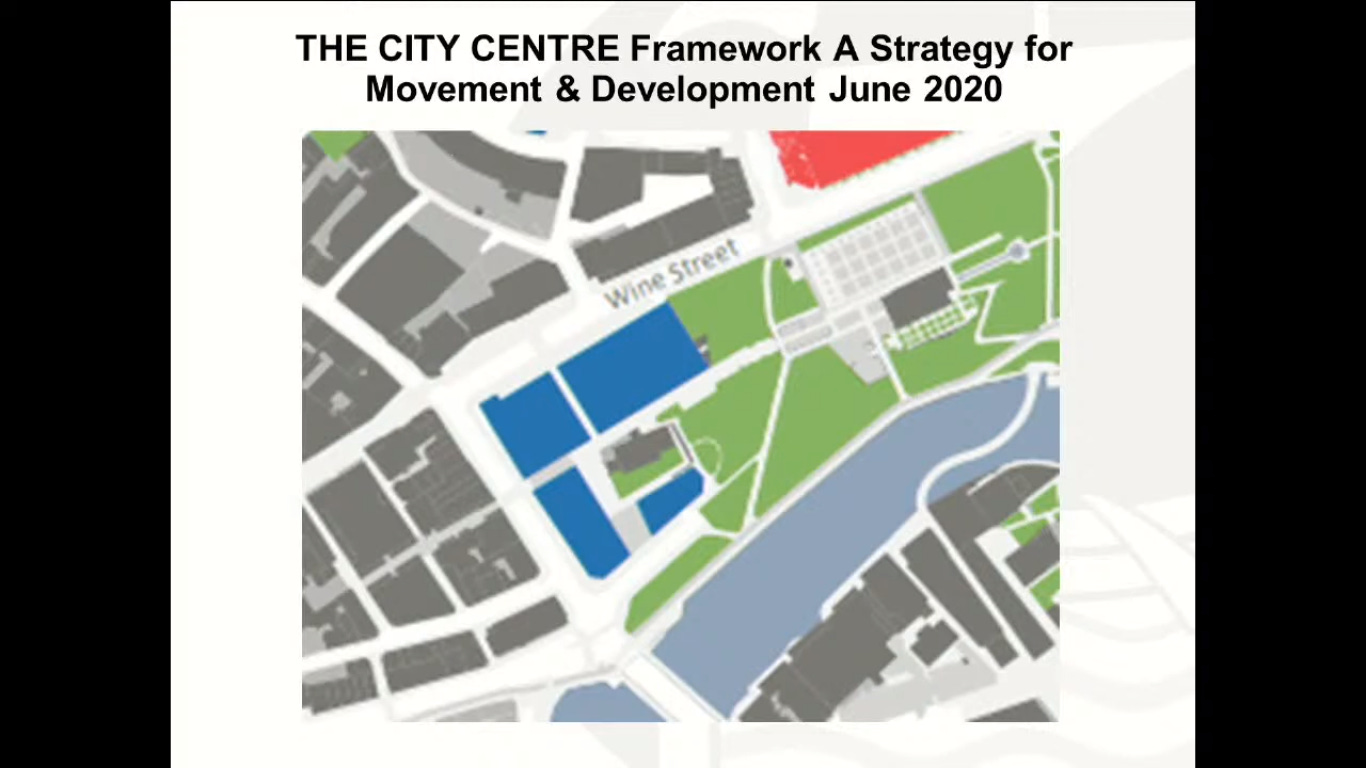

With this slow process playing out, it was important for Rees and his administration to bring in what planning documents they could to help shape development in the city. This was achieved through a Supplementary Planning Document (SPD), ‘Urban Living: Making successful places at higher densities’, adopted November 2018, and a spatial framework called the City Centre Framework, adopted June 2020. Though meant to be given less weight than the local development plan policies, they are both a material consideration in assessing planning applications.

The ‘Urban Living’ SPD would replace a 2005 SPD on tall buildings that stressed the great caution required in siting new proposals appropriately within Bristol’s cityscape.

The initial draft consultation document, published in February 2018, opened with a foreword by Marvin Rees that didn’t appear in the final approved document published later in the year. Although it repeated the idea that he wanted “Bristol’s skyline to grow”, it struck an an emollient tone that was never to be heard again:

“I acknowledge that higher density development - particularly tall buildings - is an emotive subject both for and against; advocates suggest tall buildings represent ambition and meet growth requirements, while those against often cite the need to protect the unique character of the city, and voice concerns that we do not repeat the mistakes of the past.

Both positions are valid. Bristol has a unique context, and with more heritage assets than any other UK Core City, is more sensitive to the impacts of higher density development. Meanwhile Bristol’s reputation as one of the most liveable cities in the UK is helping to attract people and investment, which places significant pressures on land use to fulfil the city’s ambition and meet growth requirements.”30

This foreword was replaced by one by Nicola Beech that didn’t dwell on this conflict. And the rest of the document ignored the results that had come back from the public consultation. The more than 600 respondents were overwhelmingly hostile to tall buildings. For example, in response to the statement: “New buildings should be allowed to be significantly higher than those around it”, 66.5% strongly disagreed, and 15.51% disagreed.31

The new ‘City Centre Framework’, approved 2020, again sought to create a easier policy environment for tall buildings. This was a spatial framework that provides detailed guidance about the city centre, layout and design of new developments. The difference between the draft produced in 2018 and the final version shows the evolving approach in terms of tall buildings and other priorities.

The Bristol Civic Society’s response to the draft version in 2018 had said:

“In particular, we strongly support the proposal to keep the building height at the prevailing city scale close to the Old City, eg at the St Mary le Port site, and do not see the approval of a tall building on the ambulance station site at the opposite corner of the park [‘Castle Park View’] as a valid precedent for the St Mary le Port site.”